Isle of Wight Nostalgia - Geology

How the Island was formed

The oldest rocks visible on the Island which contain the bones of reptiles, including

dinosaurs, were laid down about 110 million years ago when the English Channel and much of southern England formed part of the valley of a large river.

Later the area sank and was invaded by a gradually deepening sea which laid down sands and clays. As the sea became deeper a new type of

deposit was laid down; the Chalk. This is a limestone formed from the fossilised skeletons of microscopic planktonic algae. Over millions of years the slow accumulation of their remains built up the great thickness of Chalk that we can see in Tennyson Down.

About 70 million years ago the sea bed rose, was eroded and then sank beneath the sea again. This new sea was very shallow and land was never far away. It laid down a series of sands and clays which can be seen in the multi-coloured cliffs at Alum Bay. Gradually the sea silted up and the area became converted into a landscape of lagoons and marshes. At this time, about 40 million years ago, the climate of the Island was sub-tropical and crocodiles swam and crawled through the swamp.

Some 30 million years ago the situation changed once again. Stresses within the Earth's crust buckled and folded the rock layers, which were then uplifted and eroded. Gradually the Island began to assume its present shape, although until very recently (on the geological scale) it remained attached to the mainland to the north, roughly where the present Solent runs, was a great river, the so-called Solent River which drained a large area of central-southern England. About ten thousand years ago, sea levels began to rise and the great ice sheets of the last Ice Age melted.

As sea level rose, the estuary of the Solent River was gradually inundated until eventually the Isle of Wight became separated from the

mainland. This is thought to have occurred about 7,000 years ago.

Rocks

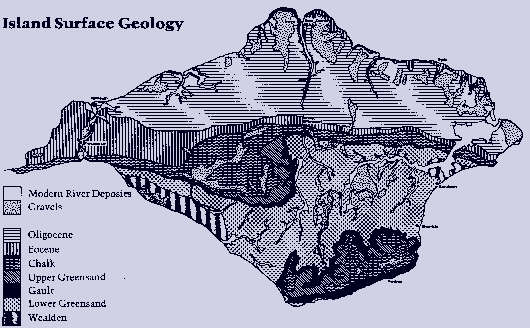

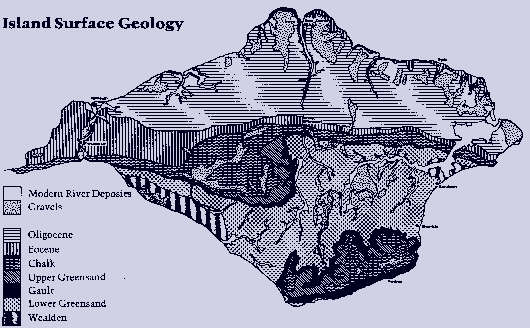

All the rocks which underlie the Isle of Wight are of sedimentary origin (i.e. they were laid down layer upon layers under water). After deposition the rock layers were buckled or folded by pressures within the Earth's crust. As the folding took place, the surface rocks were gradually eroded to produce the geology we see at the surface today. The nature of these rocks and the fossils they contain provide clues to the environments that existed in this area over the last 120 million years or so.

Cretaceous

The Cretaceous rocks underlie most of the southern half of the Island. The lower part of the sequence is composed of clays and sandstones but the upper part is made of very conspicuous white limestone, the Chalk. The local rock sequence and environmental interpretation are summarised below. Age 65 million years (Chalk) to 110 million years (Wealden)

| Rock | Character | Environment |

| Chalk | White limestone | Shallow warm sea; no land nearby |

| Upper greensand | Grey sandstone | Shallow to very shallow sea close to a shoreline |

| Gault | Black clay |

| Lower greensand | Mainly red-brown sands & sandstones |

| Wealden | Grey clay | Coastal lagoon |

| Red clays & sandstones | Flood plain of a large river |

Palaeogene

Palaeogene underlies the northern half of the Island. These are a complex sequence of clays and sands that are summarised in the table below. Age 35 million years (Solent) to 54 million years (Reading)

| Rock unit | Character | Environment |

| Solent group | Mainly green & brown clays | Lakes, marshes & coastal lagoons |

| Barton sands | White sands | Beach |

| Barton clay | Grey clays | Shallow warm sea |

| Bracklesham group (including Alum Bay sands) | Complex sequence of multi-coloured sands, grey clays | Shallow sea & river delta |

| Thames group | Brown clays | Shallow muddy sea |

| Reading clay | Red clays | Coastal swamp |

Post-Palaeogene

The Cretaceous and Palaeogene rocks were folded in the late Palaeogene and a long period of erosion began about which little is known. Scattered over the Island are various kinds of gravels. Most of these appear to have been deposited by rivers in the last half a million years but little further information is currently available.